As early as the 1970s, the term “leaky gut” was used by researchers to describe increased intestinal permeability, or the ability of substances to easily pass out of the gut into the bloodstream, provoking an inflammatory response from the immune system. These researchers linked leaky gut to certain gastrointestinal autoimmune diseases such as celiac disease. Since then, interest in leaky gut has grown and researchers continue to search for ways to target intestinal permeability in the hopes of treating autoimmune disease.

Despite growing research on intestinal permeability and its link to chronic inflammation, leaky gut is still not a medically recognized disease. In this post, we dive into how leaky gut syndrome occurs, what the root causes are, and leave you with holistic healing methods to rebuild a healthy intestinal lining. (Source)

What Is Leaky Gut?

Leaky gut is a condition that results from a damaged gut lining, but what makes up the gut’s lining and how does it become damaged?

The gut, also known as the gastrointestinal (GI) or digestive tract, consists of a chain of organs that run all the way from the mouth to the anus. Leaky gut occurs in the small intestine, which comes after the stomach and before the colon. The inner lining of the small intestine is made of a single layer of epithelial cells coated in a mucosal membrane, creating a barrier between the GI tract and the rest of the body.

When this barrier is healthy, it keeps pathogens and harmful particles out of your body, while letting water and micronutrients in. Stress from inflammation, allergens, pathogens, and autoantibodies can damage the protective mucus and weaken the tight junctions connecting epithelial cells. This increases the permeability of the lining, resulting in a “leaky” gut that allows pathogens and inflammatory particles to pass into the body and stimulate the immune system.

Cellular pathway disruption can also lead to leaky gut. Our cells rely on pathways to communicate across our bodies. For example, a nerve cell must use a cellular pathway to signal a muscle cell to create movement. When certain pathways are disrupted, membrane cells aren’t able to send the signals needed to maintain the gut barrier.

In both cases, increased membrane permeability can eventually lead to openings in the gut lining. These openings allow harmful substances and pathogens from the gut to “leak” into the bloodstream. We call this increased intestinal permeability, or leaky gut. (Source, Source, Source)

Signs and Symptoms of Leaky Gut

It is thought that leaky gut allows bacteria and other substances to escape the gut and travel via the bloodstream to other parts of the body. When this occurs, the immune system is activated in the gut, which may lead to an autoimmune disease or make a pre-existing autoimmune disease worse. However, more research is needed to determine whether this causal relationship exists.

Common symptoms attributed to leaky gut include:

- excessive cramping and gas

- abdominal bloating

- food sensitivities

- brain fog

- nutrient deficiencies

(Source)

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

Inflammatory bowel disease includes both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Symptoms include bloody stools, weight loss, diarrhea, fatigue and abdominal pain. (Source)

Celiac Disease

Celiac disease occurs when the immune system attacks the epithelial cells that line the small intestine in response to dietary gluten, increasing gut permeability. Symptoms include diarrhea, bloating, constipation, weight loss, and abdominal pain. (Source)

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

Lupus is an inflammatory autoimmune disease that affects many parts of the body and has been associated with leaky gut. Symptoms include sensitivity to sun, facial rashes, fever, joint pain, weight loss, fatigue, and kidney and renal issues. (Source, Source)

Causes and Triggers of Leaky Gut

Causes of Leaky Gut

Although it is difficult to pinpoint what exactly causes the lining of the gut to become more permeable, there are a few factors that are thought to contribute to leaky gut.

Diet

The food you consume greatly affects your gut health, which in turn can affect the health of your intestinal lining. A diet that is heavy in inflammatory foods has a number of negative health consequences, one of which may be leaky gut. Excessive amounts of refined seed oils, gluten, processed sugars, chemical food additives, pesticides, and dairy products have been linked to inflammation. Because all the food we eat passes through our gut, it’s theorized that an inflammatory diet can contribute to a leaky gut.

Fiber is also essential to cultivating gut health because it feeds our microbiome, which in turn keeps the growth of bad bacteria at bay. A low fiber diet can lead to a thinner mucus membrane and increase the permeability of the gut lining. (Source, source)

Prolonged Stress

Chronic mental stress or exposure to a prolonged stressor such as chronic alcohol consumption can negatively affect the community of microorganisms that live in the gut. These microorganisms are important in maintaining intestinal homeostasis.

When prolonged stress disrupts the gut microbiota, the mucosal membrane can be impaired. There is also evidence that prolonged mental stress weakens the immune system. Over time, this may result in decreased removal of toxins in the gut, which in turn damages the gut lining. (Source, Source)

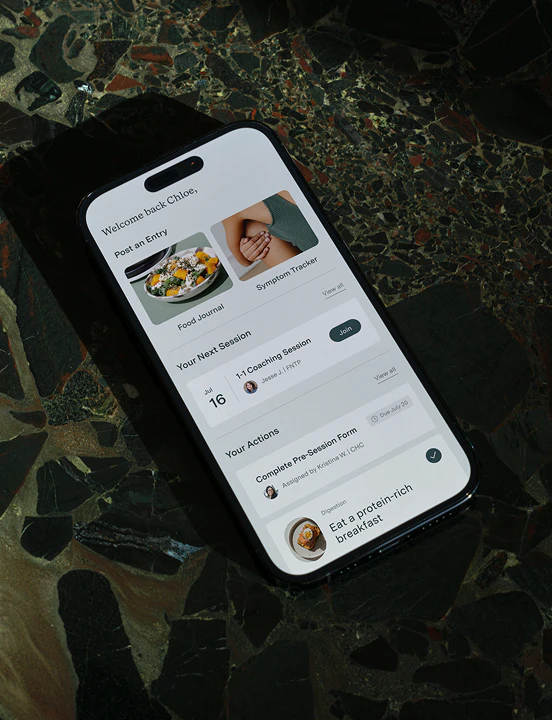

Gut Infections

If you have a stomach infection caused by a bacteria or virus, your gut can be negatively affected. A balanced gut microbiota is important for maintaining the integrity of your intestinal lining. Harmful bacteria and fungi can infect the gut and cause small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) or gut dysbiosis. Your WellTheory team can guide you through microbiome testing to identify any gut infections and empower you with treatment options for rebalancing your microbiome. (Source)

Triggers of Leaky Gut Flares

Generally, the term flare is used to describe a period during which you experience active symptoms of a given condition, and your condition “flares up.” This is thought to happen with leaky gut.

Leaky Gut Flare Triggers

- Processed foods, as well as food allergens, may cause inflammation of the gut. If you have leaky gut, your gut lining is more permeable and has developed openings that food allergens may pass through. This may cause you to feel worse after eating a meal that contains too much of these inflammatory foods.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin and ibuprofen, can damage the gut lining and allow contaminants to flow from the gut to the bloodstream. Use of these types of drugs may trigger leaky gut flares.

- Radiation treatments and chemotherapy can damage good bacteria in the gut and disrupt the gut microbiota. This imbalance can further damage the gut lining and lead to a leaky gut flare.

- Excessive alcohol consumption can cause a leaky gut flare because alcohol damages the cells that form the gut lining. There is evidence that people who drink heavily have increased intestinal permeability to the point where large molecules can pass through the gut lining. Excessive alcohol consumption also promotes inflammation in the gut, which may trigger leaky gut flares.

Managing Leaky Gut Flares

Although there are no approved drug treatments to repair the gut lining, you may be able to avoid triggers for leaky gut flares by:

- lowering your consumption of processed foods

- avoiding foods to which you are allergic or sensitive

- limiting use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories such as aspirin and ibuprofen

- limiting your exposure to radiation, if possible

- lowering your alcohol consumption

.avif)

%20(1).avif)

%20(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%2520(1).avif)